Our world is experiencing multiple crises. Investing in girls’ and women’s right to education is essential to build peaceful, just, equitable and inclusive societies; to ensure gender equality; and for the lasting protection of the planet and its natural resources. We need to invest in education to make it universally accessible and empower every girl.

Despite progress, gender disparities persist in access, completion, skills and the quality of education.

ACCESS

-

-

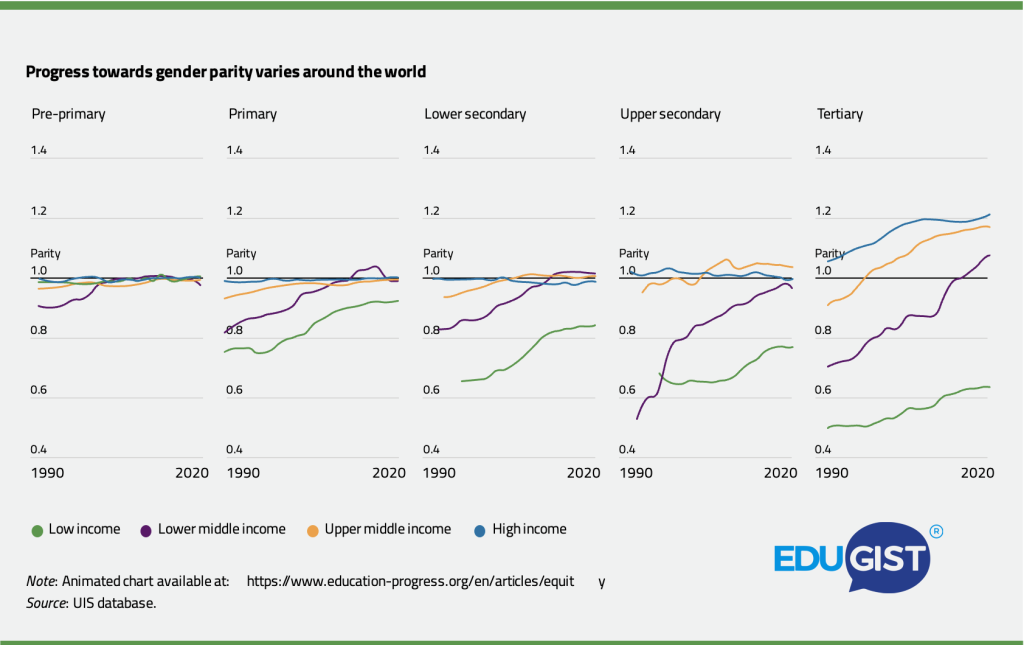

- The world achieved gender parity in the gross enrolment ratios in primary and lower secondary education in 2009 and in upper secondary education in 2013. But this still leaves 122 million girls and 128 million boys out of school in all 3 age groups combined.

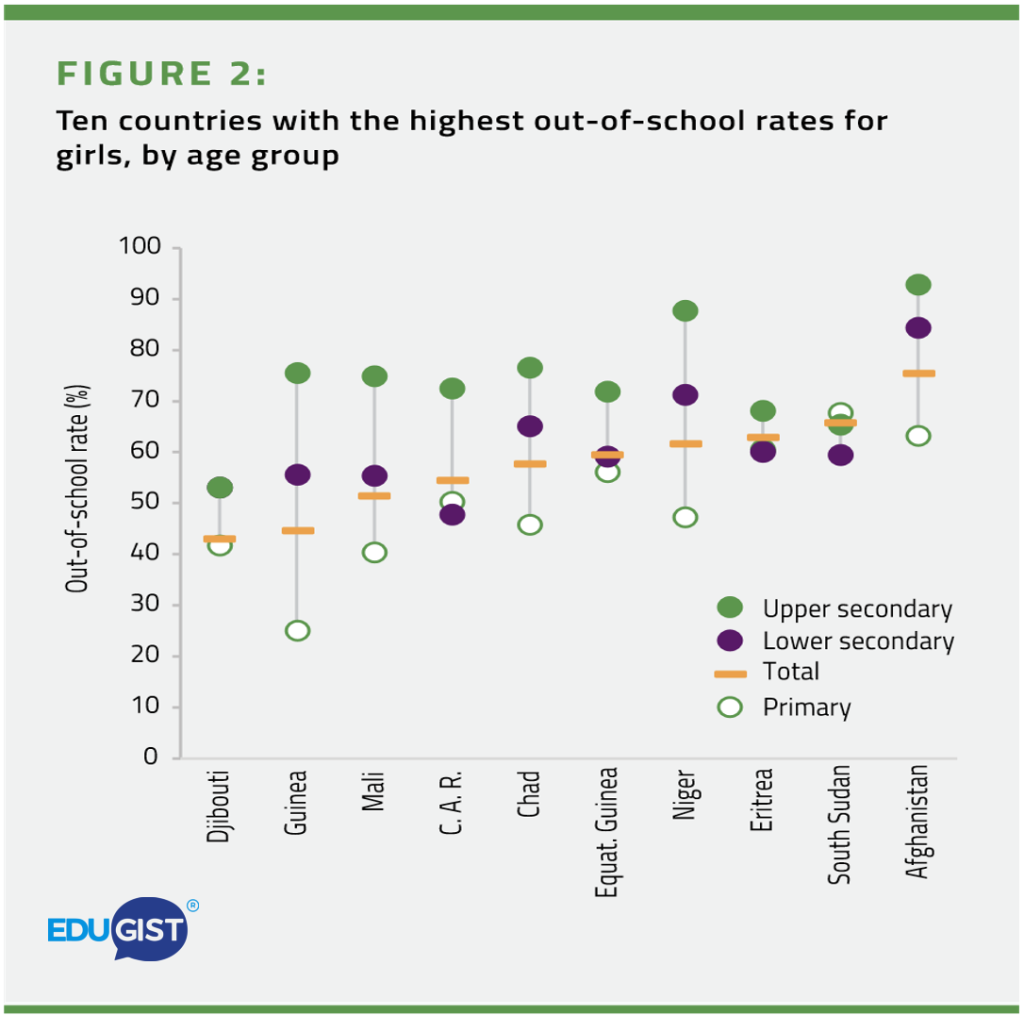

- Globally, the gender gap in the out-of-school rate among upper secondary age youth fell from four percentage points in 2000 to zero in 2020. But there are six country patterns. Three groups of countries had an initial gap in favour of boys, which either remained constant (e.g. Guinea), declined (e.g. Sierra Leone) or even reversed (e.g. Cambodia). Another group of countries maintained parity throughout (e.g. Ecuador). The other two groups of countries had an initial gap in favour of girls, which fell (e.g. Mongolia) or remained constant (e.g. the Philippines).

- Within countries, girls’ disadvantage is exacerbated due to location. In Mozambique, there are 73 young women in school for every 100 young men. But while there is gender parity in urban areas, there are 53 young women in school for every 100 young men in rural areas.

- Disparity is even more exacerbated in terms of wealth. In Côte d’Ivoire, there are 72 young women in school – but only 22 poor young women – for every 100 young men.

- In sub-Saharan Africa, gender parity has not been achieved at any level of education. As of 2020, for every 100 boys, there were 96 girls enrolled in primary, 91 in lower secondary and 87 in upper secondary. However, between 2015 and 2020, the gender parity index in upper secondary enrolment improved at the fastest rate ever observed, from 81 to 87.

-

COMPLETION

-

-

- Being enrolled is only a step towards completing each education level. Globally, gender parity in secondary completion was achieved in 2010, but by 2017, there was disparity at boys’ expense, with 95 young men completing upper secondary school for every100 young women.

- The gender gap in upper secondary completion rate is the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 benchmark indicator on equity: only 36% of countries have submitted 2025 and 2030 benchmarks. Countries where young women were at a disadvantage in 2015 reduced the gap from 6.9 to 4.2 percentage points by 2022. But while 80% of low-income and 51% of lower-middle-income countries made fast progress, countries such as Afghanistan, Benin and Nigeria regressed.

- In two SDG regions, there is disparity in secondary completion at the expense ofyoung women:

- In Central and Southern Asia, disparity remains despite progress: for every 100 young men who completed secondary school, there were 68 young women in 2000 but 94 in 2020.

- In sub-Saharan Africa, young women started from a less unequal position (75 young women for every 100 young men completing in 2000) but progressed at half the rate of Central and Southern Asia, where it was 88 young women in 2020.

- Late enrolment and repetition remain a major barrier for young women’s school trajectories in sub-Saharan Africa. Young men can afford to be late completers but young women who are not on course to finish upper secondary school on time are under pressure to marry and have children. There has been no progress in addressing this challenge in the past 20 years. So while 88 young women complete secondary school on time for every 100 young men, ultimately only 79 young women do so.

-

LEARNING

-

-

- In reading, among 97 countries with data in upper primary and lower secondary education in 2016–19, only 2 had a tiny gap favouring boys: Chad and the Democratic

- Republic of the Congo. In the other 95 countries, the share of girls with minimum proficiency was an average of 10 percentage points higher than the share of boys. Globally, for every 100 proficient boys, there are 115 proficient girls in reading at the end of lower secondary education.

- Boys have a small advantage over girls in mathematics in primary education, but this is reversed in lower secondary education. In the 2019 Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), the share of grade 4 boys with minimum proficiency exceeded that of girls by 1.4 percentage points in 30 upper-middle and high-income countries. But by grade 8, girls had a 1.4 percentage point advantage over boys. However, these gaps relate to achieving minimum proficiency, while boys tend to have a considerable advantage over girls in mathematics at the higher end of performance.

-

STEM AND ICT SKILLS

-

-

- Gender is one of the strongest determinants of the likelihood of pursuing an education and career in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Grade 8 boys were more willing to pursue a mathematics-related occupation than their female schoolmates in 87% of the education systems participating in the 2019 TIMSS.

- There is clear gender disparity at the expense of women at low levels of ICT skills but at higher levels of some skills in the population, parity is often achieved and women may even be more likely to acquire them. Take, for instance, the skill of managing a basic arithmetic formula in a spreadsheet. In the Balochistan province of Pakistan, where 2% of adults have this skill, there are only 8 young women for every 100 young men who do. In Tonga, where 19% of adults have this skill, women are twice as likely as men to have this skill.

-

HIGHER EDUCATION

-

-

- Tertiary education progress has been different. Globally, gender parity was achieved in 1998, but by 2004, there was already disparity at the expense of men, which has continued to increase: In 2020, there were 114 women enrolled for every 100 men at this level of education. In sub-Saharan Africa, for every 100 men, there were 80 women enrolled.

- According to Her Atlas, only 9% of women enrol in tertiary education when primary and secondary education is neither compulsory nor free.

-

Investment in girls’ education has a huge societal impact

Greater agency and decision making:

-

- Achieving universal secondary education could increase women’s decision making in the household by one fifth and the likelihood that children are registered at birth by over one quarter (Wodon, Male and Onagoruwa, 2024).

Better living standards:

-

- Women with secondary and tertiary education report higher standards of living compared to those with no more than primary education (Wodon, Male and Onagoruwa, 2024).

Intergenerational benefits for health and nutrition:

-

- For children born to mothers with 12 years of education, under-5 mortality is 31% lower (Balaj et al., 2021).

- In Nigeria, universal secondary education for mothers could reduce under-5 stunting by 10%(UNESCO International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa, 2023).

End child marriage and early childbearing:

-

- Universal secondary education could virtually end child marriage and reduce early childbearing by up tothree fourths (Wodon, Male and Onagoruwa, 2024).

- Universal secondary education could reduce the number of children women have over their lifetime by onethird on average across 22 African countries (Wodon, Male and Onagoruwa, 2024).

Increased access to decent work:

-

- One additional year of school can increase a woman’s earnings by up to 20% (Wodon et al., 2018).

- Women with a secondary education are 9.6 percentage points more likely to work than those with a primary education or less. With tertiary education, they are 25 percentage points more likely to work than if they onlyhave a primary education or less (Wodon et al., 2018).

- Women with secondary education could expect to make more than twice as much and women with tertiary education almost five times as much as those with no education (Wodon et al., 2018).

- Education increases women’s access to the workplace, and wage-earning women have greater economic independence at home and in society (Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, 2022).

Economic development:

-

- Globally, the loss in human capital due to gender inequalities is estimated to be around USD 160 trillion, which is about twice the value of global gross domestic production (Wodon and De La Brière, 2018).

… and the contribution of girls and women is essential for the shift to the green economy

Investing in girls’ and women’s education is a smart investment for the green transition…

-

- For each additional year of education that girls acquire, a country’s resilience to climate disasters increases by2-3 percentage points on average (The Education Commission, 2022).

- Girls’ secondary education has been identified as the most important socioeconomic determinant in reducing vulnerability to climate change (Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, 2022).

- If the share of women receiving a lower secondary education increased from 30% to 70%, this could result in a60% lower death toll from extreme weather events by 2050 (The Education Commission, 2022).

- Once young people become climate-literate, they help to educate their families, which has a multiplier effect on their communities. The effect appears to be particularly strong when young women receive this education (The Education Commission, 2022).

- More women are likely to start a business focused on sustainability (World Bank, 2023).

- Where education opens leadership opportunities for girls as adults, their participation in national politics can lead countries to adopt more environmentally friendly policies (Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, 2022).

- Giving women greater access to leadership positions in both the public and private sectors and at all levels of decision making can help focus priorities on environmental goals (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021).

… but girls and women are less well prepared for and represented in green jobs

-

- Young people do not feel adequately prepared to go into green jobs, with young women feeling less skilled than young men. Women are already underrepresented in fast-growing green energy sectors that require high-level technical skills (UNICEF Innocenti – Global Office of Research and Foresight, 2024).

- The green jobs of the future will require STEM skills and knowledge. Yet, in 2019, in 30 out of 121 countries, fewer than 20% of graduates in engineering were women. In 61 out of 115 countries, fewer than 30% of computer science graduates were women.

elvis@edugist.org,

elvis@edugist.org,

+234 818 578 7349

+234 818 578 7349