In June 2023, as the final school bell rang out across the Nawairudeen Junior Grammar School grounds in Solu, Ogun State, Vice Principal Temitope Oniyide stepped away from her desk and made her way to the assembly grounds. There, she addressed the gathered teachers and students, congratulating them on the successful completion of the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE).

At the end of her speech, chaos erupted. Students started throwing stones in the air and screaming in excitement. The celebratory atmosphere quickly turned volatile when a heavy stone struck Mrs Oniyide, causing her to fall and sustain multiple injuries. This did not stop the students, who continued their aggressive celebrations, shattering windows and damaging several pieces of school property.

Several local reports indicate that such levels of destruction, and indiscipline displayed by the students are commonplace in both the junior and senior secondary arms of the Nawairudeen Grammar School.

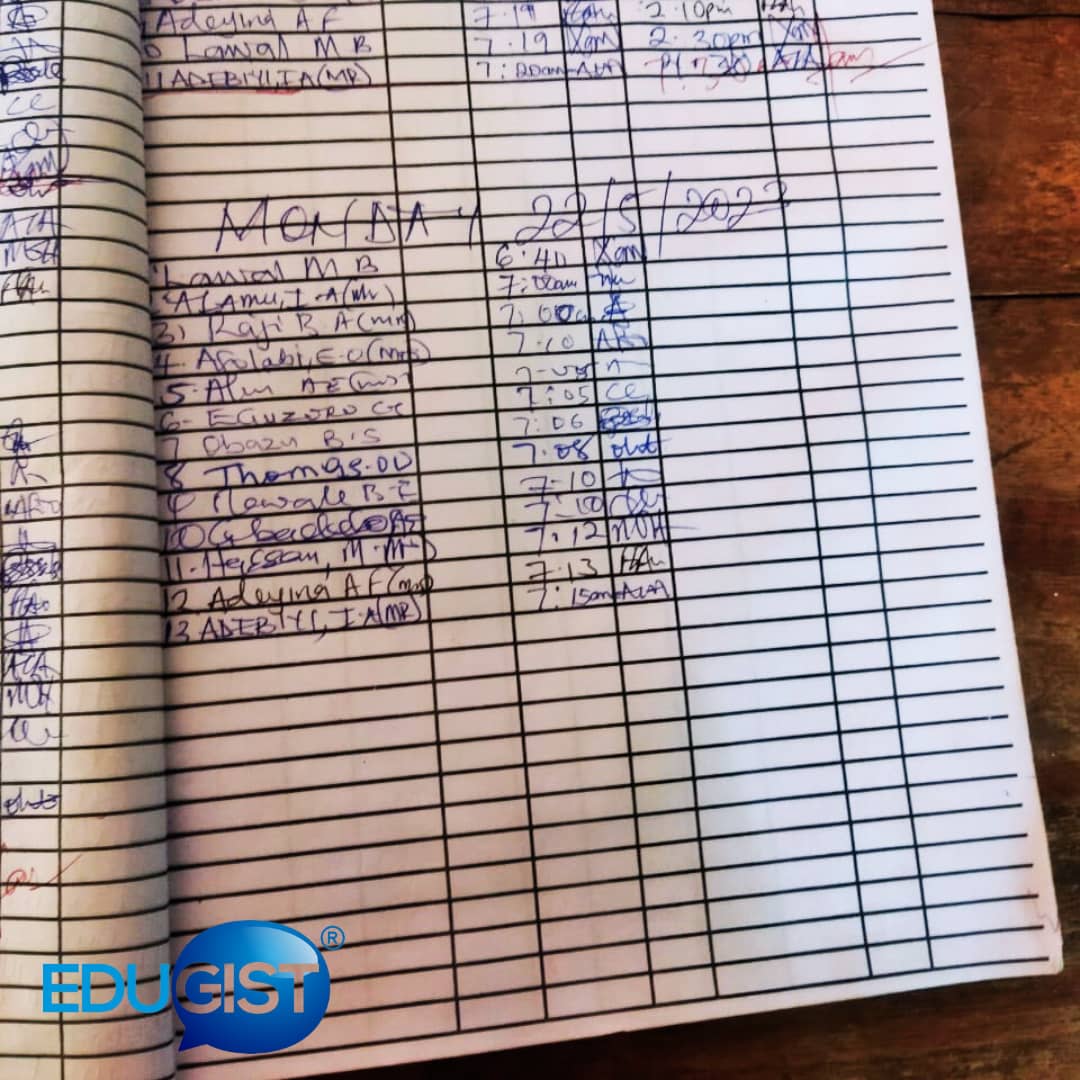

Between June 2022 and April 2023, the school recorded over 15 cases of violence and harassment perpetrated against school teachers. According to Mrs Oniyide, these numbers used to be much higher.

“We have recorded over 55 cases of students attacking teachers in the last two years, particularly during the May and June exam periods,” Mrs Onyide revealed in an interview with this reporter.

When these incidents happen, the school authority reports the culprits to the community leaders and sometimes the police. However, it often results in ineffective disciplinary measures.

“The students get away with a warning or end up in jail at the local police station for a few days before they’re released,” Mrs Oniyide said.

It started long before now

Solu, a developing community in Ifo, Ogun State, is dominated by traders and migrants from nearby Lagos. As a rural area, Solu did not have access to formal education until the early 2000s. The arrival of a local school marked significant progress for the community, as it did for many others across Ogun State. However, 83-year-old Solu chief and veteran educator Bashorun Bode Sogunle reports that the early years of the school were marred by numerous incidents of assaults, molestation, and other forms of harassment involving the school community. According to Sogunle, these safety issues quickly made teaching in Solu a dangerous prospect for educators.

Bashorun Sogunle believes the root cause of the conflict in those early days was the small age gap between teachers and students.

“It contributed to a lack of authority and respect.

“Trading was considered more important than education in this community, so the student population in the early days was between ages 17-21,” Bashorun Sogunle told this reporter in an interview.

This age group, as scientific research indicates, exhibits a heightened degree of “youthful exuberance,” which can manifest in disruptive behaviours. In the case of Solu, the students became a danger to the community.

With 10-15 teachers responsible for over 1,500 students in Nawairudeen school, the shortage of teaching staff was an attributable factor that led to frequent attacks on teachers.

The teachers, on the other hand, were defenseless against the students for many reasons but most recently due to a state government-imposed ban on corporal punishment in public schools. This, Bashorun Sogunle explained, further undermined the authority of teachers in the school.

Attacks on teachers were further exacerbated by insecurity. With no perimeter fencing, anyone could access the school even at odd hours.

“During school hours, you will even see hawkers entering the school to sell their goods because there is no fencing, Ademilola Daramola, a former student said during an interview.

Now a mechanical engineer, Daramola, recounted how senior boys formed cult groups and perpetuated evil in school.

“The senior boys ruled the school. Some of them belonged to cult groups. That’s why they controlled us and didn’t obey the teachers at all,” Daramola said.

Teachers Must Be Protected

After several failed attempts to protect teachers, Solu community leaders and school administrators decided to work together.

First, the community, led by Bashorun Sogunle, invested in constructing a dormitory facility to house teachers and non-local students attending the school. According to Lasisi Olagunju, the senior secondary school principal, this new housing option served as a level of protection outside the school grounds for teachers.

“We also hired a vigilante group who started to patrol the school premises.

“As a local community, we had to organise ourselves to be able to afford paying the group. Their duty was to keep an eye on any student misbehaving and get them arrested for sanction,” Olagunju explained.

When erring students are apprehended by the local vigilante group, a policy overseen by Olagunju comes into effect. This policy, consented to by parents, mandates that such students be sent to the local police cell and only released upon their parents’ purchase of five building blocks and a bag of cement. These materials were allocated for fencing the school.

Within the three months, the school fencing project had been completed halfway. However, the transfer of Olagunju away from the school abruptly halted progress.

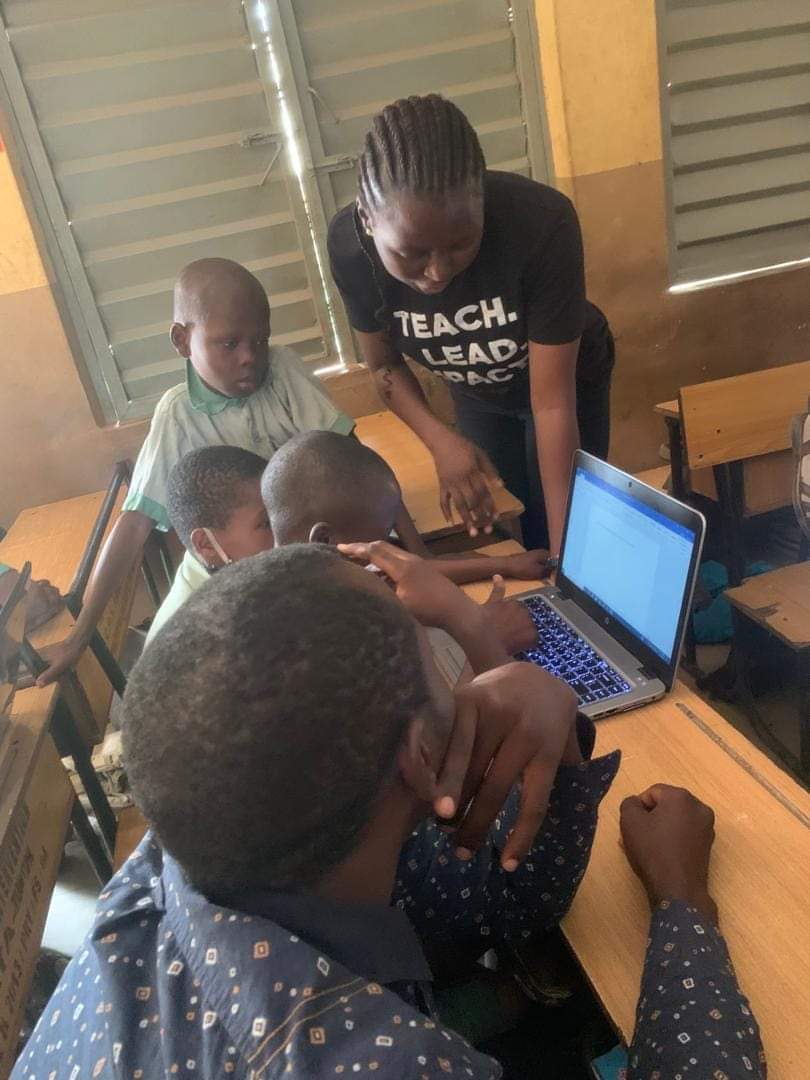

To increase the number of school teachers, Nawairudeen Grammar School also signed up to join the Teach for Nigeria Fellowship Programme.

Launched in 2016, the programme supports the recruitment of young professionals from all disciplines to teach as full time teachers (fellows) in underserved schools in low-income communities like Solu.

After partnering with TNFP, Nawairudeen school welcomed its first cohort of two educators in September 2023. Their presence not only augmented the teaching force but also injected fresh perspectives and innovative approaches into the classrooms.

The Teach for Nigeria Fellowship Programme

To take it a step further, the school administrators also organised sensitisation workshops and seminars for parents during weekends.

The initiative, supported by Bashorun Sogunle, other local chiefs, and the Baale (Village Head), prioritised engaging educated sons and daughters of the community to sensitise parents. During these meetings, essential topics such as peacekeeping, tolerance, and effective parenting were covered. The workshops drew significant participation, with over 300 parents and community members attending.

Mrs. Abimbola Ayoade, one of the parents of a senior student who attended one of the workshops, said that the workshops were enlightening, as many parents struggled to instill discipline in their children.

“I must commend the community and school for the workshop,” she said, reflecting on the initiative. “But many parents didn’t attend. Most of the students here have parents who aren’t really interested in school activities. They just see the school as a dumping ground.”

She believed the workshop highlighted a crucial issue: the need for greater parental involvement in their children’s education. However, she felt that the workshops were not enough.

“The community should not only bring parents together but introduce heavier sanctions on parents whose children misbehave,” she suggested.

Work in progress

Despite still struggling to completely eliminate disorderly conducts of some students, Bashorun Sogunle says peacekeeping programs have yielded some results.

“We’ve seen a decrease in teacher harassment by students, but we still get few complaints from school administrators although not as bad as before,” he said.

On the other hand, Teach for Nigeria’s collaboration with local schools has brought renewed energy to the Solu community. Four of the program’s fellows now teach at the Nawairudeen Senior Grammar School, including Adekanbi Anuoluwapo and Agboola Kemi, who instruct Biology and English respectively.

“Things are getting better,” said Anuoluwapo, who no longer fears attacks on campus. “Before, there were no young people the students could relate to. Now, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) regularly donate books and supplies to boost learning.”

Fellow teacher Kemi also highlighted improved living conditions for educators. “Teachers used to stay in Abeokuta out of fear, but now we can live near the school,” she noted.

The progress made is, however, dampened by the ban on corporal punishment, according to Bashorun Sogunle. He said the government’s stance was frustrating their efforts.

“With the government’s stance on corporal punishment, we’re falling back to the beginning. This is Africa; we believe in discipline, but it should be measured to avoid causing severe pain,” he said.

Enhancing School Security and Student Discipline: A Security expert view

Despite the improvements made, ensuring security within the school premises remains a complex challenge. Onyekachi Adekoya, a seasoned security expert with over 18 years of experience and a fellow of the Institute of Strategic Management, offered insights into the limitations and potential enhancements of the current security measures.

Adekoya emphasised the need for a comprehensive approach, stating, “The vigilantes, much like the police or military, are operatives. However, without a proper risk assessment that identifies the sources of risks and the conditions that may trigger underlying issues, the security efforts may falter. Security isn’t just a system; it’s a programme that requires careful design, appropriate resources, and long-term commitment.”

He pointed out that a thorough assessment by an expert or a dedicated committee could significantly improve the situation. “A desktop review won’t suffice,” Adekoya continued. “The effectiveness of security measures hinges on understanding the local context and implementing a well-coordinated programme. This should include multiple layers and approaches, such as stakeholder engagement, advocacy, and a review of existing security protocols.”

Addressing the specific challenges of rural schools, he noted the importance of clear boundaries. “Some of these schools may lack proper fencing, making it difficult to define safe spaces. Effective security requires not only fencing but also well-managed entry and exit points, which can be overseen by vigilant personnel.”

Adekoya further recommended the reintroduction of history and civic duties in the curriculum to foster a sense of responsibility among students. He advocated for community involvement, urging local education boards, religious leaders, and other stakeholders to collaborate in shaping students’ behaviours both at home and in school.

“Security issues require a localised approach,” he concluded. “A proper assessment and continuous improvement are essential, as transforming the culture within a school environment can take several years. It’s about phasing out negative behaviours and addressing external influences that affect students when they’re outside the school premises.”

A Comparative Look at Solu Community and the UBEC Programme

According to the Global Education Monitoring (GEM ) Report 2020, violence in schools, including violence against teachers, is a global phenomenon.

The UNESCO’s GEM report notes that teacher harassment by students is a problem in South Africa, India and Brazil which is affecting teachers’ morale and retention.

Recognising the critical importance of addressing this in Nigeria, national initiatives, such as the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) Moral Regeneration and Reorientation Programme, have embarked on efforts to promote moral values and a safe, respectful educational environment.

The UBEC programme focuses on moral regeneration and reorientation among students, aiming to instill values of respect, responsibility, and good ethics. This national-level intervention employs a multifaceted approach, emphasising family engagement, collaboration with NGOs and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), involvement of religious and community leaders, advocacy and awareness campaigns, and capacity-building for stakeholders.

Both the UBEC programme and Solu community’s efforts share a common goal: promoting moral values and character development to create a respectful and safe educational environment. Despite operating at different levels—national versus local—their strategies reveal notable similarities.

The UBEC programme emphasises the role of families in moral regeneration, encouraging parents to be active participants in their children’s moral education, while the Solu community organises training for parents, equipping them with the tools to teach their children moral values and peacekeeping skills.

Both initiatives involve the community: the UBEC programme collaborates with community-based organisations, religious leaders, and civil society organisations to foster a collective effort in moral reorientation, while the Solu community involves community members directly by employing vigilantes to monitor schools and ensure a harassment-free environment for teachers.

Advocacy and awareness are also central to both efforts, with the UBEC programme conducting campaigns to raise awareness about the importance of moral values and respectful behaviour within the education system, and the Solu community raising awareness within the community about the significance of maintaining a respectful and peaceful school environment, reinforcing the community’s role in supporting teachers.

“The impact of these initiatives extends beyond the classroom, influencing broader societal norms and behaviours,” Adekoya further highlighted.

As the sun set over Solu in the present day, the collective efforts of community leaders, teachers, and parents were evident, especially in Nawairudeen grammar school. The journey was far from over, but the foundation for a safe educational environment has been laid.

This story was produced with the support of the Solutions Journalism Network and the Nigeria Health Watch in partnership with Edugist.