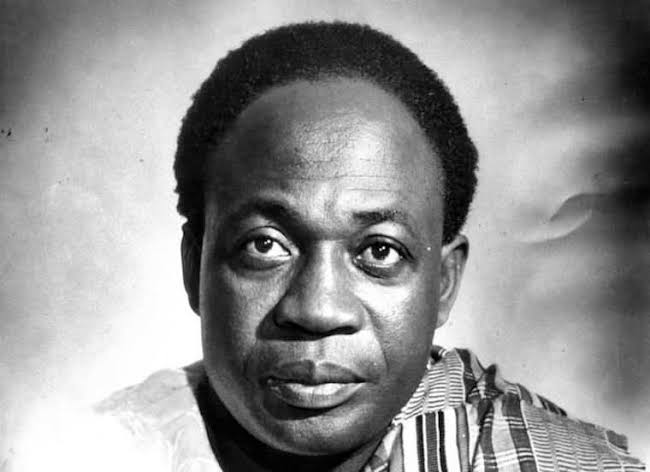

Kwame Nkrumah, a towering figure in Africa’s struggle for independence, was Ghana’s first Prime Minister and later its first President. His life was dedicated to the liberation and development of his nation and the African continent as a whole. Born on 21 September 1909 in Nkroful, a small town in the Western Region of the Gold Coast (now Ghana), Francis Kwame Nkrumah attended the Achimota School in Accra and later worked as a teacher before pursuing higher education abroad.

In 1935, he travelled to the United States to study at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, earning a Bachelor of Arts in Economics and Sociology. He continued his education at the University of Pennsylvania, obtaining a Master of Science in Education and a Master of Arts in Philosophy. During his time in America, Nkrumah was exposed to the ideas of socialism, Black empowerment, and Pan-Africanism, drawing inspiration from Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Du Bois. He later moved to the United Kingdom, where he studied at the London School of Economics and became active in African nationalist movements. Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast in 1947, invited by the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), a political group pushing for independence. However, ideological differences led him to form his own party, the Convention People’s Party (CPP), in 1949. The party’s slogan, Self-Government Now, resonated with the masses.

His activism led to his imprisonment in 1950, but the 1951 elections saw the CPP win a landslide victory, resulting in Nkrumah’s release and appointment as the country’s Leader of Government Business. In 1952, he became the first Prime Minister, steering the country towards full independence. On 6 March 1957, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence from British rule, with Nkrumah declaring, “The independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of Africa.”

In 1960, Ghana became a republic, and Nkrumah was elected its first President. His leadership was marked by ambitious infrastructure projects, including the Akosombo Dam, which provided hydroelectric power, and the expansion of education, health, and transportation systems. He aimed to transform Ghana into an industrialised, socialist state, promoting policies of economic self-sufficiency.

Beyond Ghana, Nkrumah championed the cause of African unity. He played a key role in the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, which later became the African Union (AU). His Pan-African ideals positioned Ghana as a beacon for liberation movements across the continent, supporting independence struggles in Angola, South Africa, and Zimbabwe.

Despite his visionary leadership, Nkrumah’s administration faced internal dissent. His push towards a one-party state and suppression of opposition led to growing discontent. Economic difficulties, coupled with allegations of corruption and mismanagement, weakened his popularity. On 24 February 1966, while Nkrumah was on a diplomatic trip to China and North Vietnam, his government was overthrown in a military coup. He lived in exile in Guinea, where he was granted honorary co-presidency by President Sékou Touré. He continued advocating for African unity until his health deteriorated.

Kwame Nkrumah died on 27 April 1972 in Bucharest, Romania, after battling cancer. His remains were later returned to Ghana, where he was honoured as a national hero. Today, his contributions are celebrated across Africa. His birthplace, Nkroful, and the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum in Accra serve as symbols of his enduring legacy. His vision of African unity continues to inspire leaders and scholars. His writings, including Africa Must Unite and Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, remain influential in political and academic circles. Kwame Nkrumah’s life was one of relentless pursuit of freedom and progress. His dreams for Ghana and Africa live on, making him an unforgettable figure in the continent’s history.