The Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) has rejected the Core Curriculum Minimum Academic Standards (CCMAS) that the National Universities Commission (NUC) has proposed opening up a critical window for dialogue on Nigeria’s university curriculum design.

Professor Emmanuel Osodeke, national president of, ASUU, in a signed statement on Friday, said it was unacceptable for the NUC to attempt shoving 70 per cent pre-packaged CCMAS content down the throat of Nigeria’s university system. This leaves university senates 30 per cent autonomous input, whereas they are statutorily responsible for academic programme development. Besides, the Union stated that there are numerous shortcomings and gross inadequacies in the CCMAS documents.

ASUU acknowledges that setting academic standards and assuring quality in the Nigerian Univesity System is within the remit of the NUC. However, the process of generating the standard is as important (if not more important) than what is produced as “minimum standards.”

A curriculum is what is taught in a given course or subject. Curriculum refers to an interactive system of instruction and learning with specific goals, contents, strategies, measurements, and resources. The desired outcome of the curriculum is the successful transfer and/or development of knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Legal framework

According to Section 1 of the Education (National Minimum Standards) and Establishment of Institutions Act of 1985, the minister is in charge of setting and upholding minimum standards in pre-primary and primary schools as well as other similar institutions throughout the federation.

Section 4 of the same act provides that the responsibility for the establishment and maintenance of minimum standards in secondary schools and higher institutions in the federation shall be vested in the minister.

Section 10 of the same act, provides that the power to lay down minimum standards for all universities and other institutions of higher learning in the federation and the accreditation of their degrees and other academic awards is vested in the National Universities Commission, the former in consultation with the university for that purpose after obtaining prior approval through the minister from the President.

These are the minimum standards of what educational institutions must teach their students. The law makes no mention of a review time or considerations for a review. As a result, the government controls the curriculum in this country and this has been so for many years.

The bickering between ASUU and NUC is an offshoot of this legal framework. The Union of university dons claim it has not been duly consulted and the legal framework that provides for the setting of minimum standards prioritises the executive powers of approval vested in the minister of education as a representative of the president of Nigeria. The process of generating the minimum standards is as important as the minimum standards formulated.

Government-led curriculum in a market economy

While we let ASUU wrestle with the NUC to secure more than 30 per cent autonomous input into curriculum design for Nigerian universities, we have a bigger fish to fry. Our bone of contention questions the process through which both the NUC and universities decide what goes into the curriculum. But let us first address the elephant in the room, a government-led curriculum design in a market economy.

In a market-driven society, a government-driven curriculum cannot be successful, particularly at the post-secondary education level. Government has a dual responsibility for the inadequate creation and execution of curricula in Nigeria’s educational institutions. Government policies on education make up the first, while regulations make up the second.

Allowing professionals in Nigeria to build a curriculum that will help them stay relevant in the market is essential if they want to stay competitive and effective. In fact, at their origins in the medieval period, universities and their curriculum were built around guilds, that is, associations craftsmen and merchants. Of course, this has evolved.

However, in contemporary societies, the associations that professions establish meet on a regular basis to discuss how to advance their fields. On the basis of market realities, they must also decide what core competencies and soft skills their members need to possess in order to remain competitive. For instance, a doctor may find it useful to have talents in the fine arts, whereas a lawyer may find marketing and management skills necessary.

How else would she be able to sketch or understand computer illustrations of those intricate organs that are typically found in foreign textbooks? No profession exists in isolation in countries where things are going well. After finishing their basic education and continuing to work in such industries, people are urged to specialise and expand their competencies in affiliate programmes.

The education and practice of the profession will be able to take a holistic approach as a result. Furthermore, every institution must identify its areas of comparative advantage and create a curriculum that will support those areas.

For instance, given the current large-scale farming in Northern Nigeria, one would have assumed that the region would have seen the emergence of numerous agricultural universities with specialised, highly commercialised curricula leading to degrees and vocational certificates, particularly in the areas of mechanised farming, the development of improved species, and an efficient system for storing products that are driven and proven by the market. But Nigeria’s university system is fraught with even more insidious government distortions.

The division of funds between private and public institutions is arguably the worst way that government decisions have harmed the development of curricula. Government policies favour public-sector funding of research over private-sector funding.

This segregation is typically justified by a lack of sufficient government financing. ASUU and the Federal Government have been going back and forth in a trade dispute. While the Federal Government asserts that it lacks the necessary cash to pay ASUU, without which the government would be unable to function, ASUU says that the government has broken its agreement with it by failing to release money that should have been released for funding university research.

Both arguments are out of place. This is due to the fact that financial investments should be considered while developing new curricula that will educate and execute the results of the new study. When someone finds that a specific study outcome is profitable through adequate feasibility studies, she typically does everything in her ability, including borrowing, to fund the endeavour.

The evidence that the research funding ASUU is requesting will produce a quantifiable benefit for the nation’s progress, independence, and economic sustainability is what the government should seek from ASUU.

When seen from this angle, it becomes clear that a university or academic staff cannot receive research funds solely because they exist or because they are employed. It will be distributed exclusively to institutions and people who have shown viable research ideas for satisfying such demands, based on the crucial areas of need of society and in conformity with the government’s development goal.

Therefore, it is irrelevant whether a researcher works for a private or public institution or whether the institution is public or private. The government cannot be encouraged to simply say “no” to requests for effective funding of research in these institutions, but it also cannot afford to throw money at educational institutions for research carelessly.

Working it out

To wrap up, we will outline the essential considerations in curriculum development and show how they can be met through the solution that we shall propose.

The essential considerations for curriculum development comprise, identifying an issue, a problem, a need (what), determining the characteristics and needs of learners (who), delineating changes intended for learners (intended outcomes), formulating important and relevant content (what), specifying methods to accomplish intended outcomes (how), evaluating strategies for methods, content, and intended outcomes (what works?).

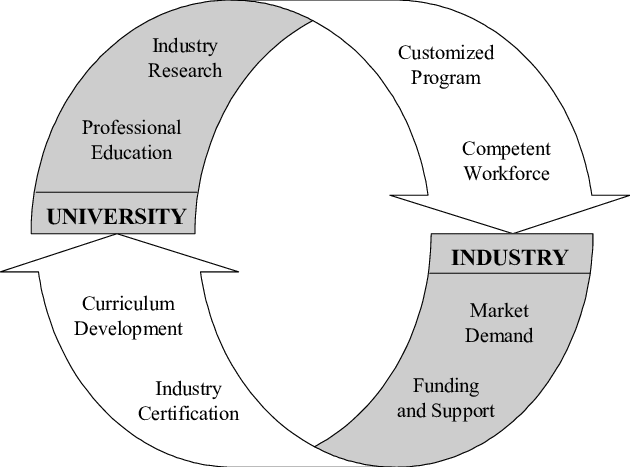

From the essential curriculum considerations that we have outlined, we can safely deduce that a government-led curriculum design would be flawed without the collaborative input of universities, captains of industry and students. If ASUU cries foul because it has not been duly consulted, we wonder whether captains of industry and students were consulted in arriving at the CCMAS. How would NUC articulate the essential elements of a curriculum without a broad-based consultation?

For instance, to understand the problems of an industry, professionals from that industry have to be consulted. To determine the characteristics of learners, the universities have to be in the picture. Intended outcomes and relevant content are both functions of market conditions, which require wide consultations with industry practitioners and professionals.

In saner climes, as we say, universities frequently work with a variety of persons and groups to develop their curricula and syllabi. The university’s academic administration is in charge of supervising the creation and execution of the syllabus and curriculum on a high level.

At most universities, there is a curriculum committee or academic council that is responsible for designing and revising the curriculum. This committee typically includes faculty members from different departments and academic disciplines, as well as representatives from student organisations, academic support services, and the university administration.

In addition to these groups, universities consult with external stakeholders such as employers, industry leaders, and alumni to ensure that the curriculum is relevant and responsive to the needs of the job market and society.

Overall, the design of curriculum at universities is a collaborative effort involving multiple stakeholders and takes into account a variety of factors, including academic standards, student needs and interests, and societal demands. This is why the NUC has to backtrack and consult properly. And it is also time to turn the tables and have a curriculum that is responsive to market demands – market-led not government-led. Otherwise, graduate unemployment will keep rising.