Children are the best hope for the future in every society. For this reason, special attention is given to their education and development. Alluding to this cause in Africa, the African Union (then known as the Organisation of African Unity) initiated the International Day of the African Child, observed every June 16th to raise awareness of the continuing need for improvement of the education provided to African children.

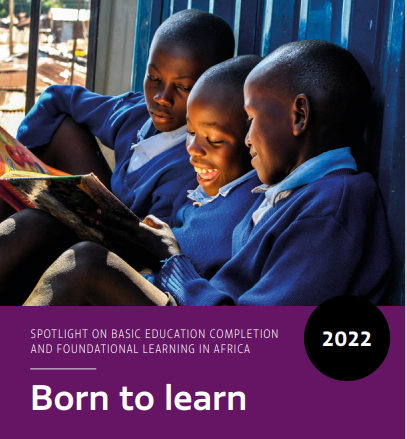

While the 2023 theme focuses on ‘the rights of the child in the digital environment’, a report, Born to Learn recently launched by the United Nations Education Science and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Global Education Monitoring Report Team unearths more serious concerns on foundational learning.

According to the report, in sub-Saharan Africa:

- One in five primary school-age children are out of school

- Only two in three children in the region complete primary school by age 15. Among those who do, only three in 10 achieve the minimum proficiency level in reading

- For every 10 children who complete primary education, only two are able to read and understand what they are reading

- Essentially, Children in Africa are five times less likely to learn the basics (this implies that foundational learning is poor)

The report, which is the first of the spotlight series aimed at turning the hopes and dreams of African children into reality, also provides recommendations on what Africa needs to do to address these concerns. During a chat with the Edugist team, the Senior Project Officer (Spotlight technical lead), at UNESCO GEM Report, Patrick Montjouridès shares insights from the report and how African Nations like Nigeria can address the foundational learning crisis.

What are your thoughts on the African Child?

African children are children like any other. However, they tend to face more hardships when compared with other children in general. One of the big differences is that they have to do much more to have their right to education fulfilled.

Why is it important to spotlight the aspect of learning at a time like this?

This is why we actually launched the #borntolearn campaign. The campaign aims to remind us all – government, citizens, and parents that children are born with the same right to education and we are all duty-bearers of this right. Unfortunately, most African children are born with limited chances of accessing school or even learning basic reading and mathematics skills.

So, what I have observed from available data is that the African child is five times less likely to complete basic primary education and to learn basic literacy and numeracy skills when compared with any other child in the world. That means that not only in many instances African children do not complete primary education but also do not get to learn even when they manage to sit in the classroom, and we think it is very important for us to remain aware of these issues.

Eventually, the Born to Learn campaign and spotlight series builds on the findings of the Born to Learn report and is at the intersection of evidence, science, advocacy and policy-making. It also calls for a corrective action that will address this legacy of neglect that the education systems in Africa has been subjected to, particularly when it comes to imparting children with the basic building blocks of development and consequently the future development of Africa.

Why is foundation learning so critical to children?

For us, it is very simple. Foundational learning which not only includes basic literacy and numeracy skills but also social-emotional learning is the building block of any future educational human and institutional development. If you don’t know how to read for comprehension or to execute basic mathematics operations, you will not be able to fully participate in other learning experiences and even less, be able to learn on your own at home with textbooks, on-screen, or using an application.

If you don’t get foundational learning from the onset, you are already cut off in your pursuit of physio-educational, social, and human development. That is why foundational learning is so critical.

Earlier you mentioned that African children have been victims of neglect and this has adversely impacted their educational development. Aside from neglect, what other challenges do African children face?

There are different aspects of these challenges and some are associated with systems. Some of the challenges affecting this population set have to face, emerge from the fact that education systems in the region are yet to be able to adequately accommodate all children. Closely linked to this accommodation issue is the rapid demographic growth that continues to pressure African systems. For instance, many African countries have had tremendous progress towards guaranteeing access to education to more children and this should be celebrated as this is the fastest progress we have witnessed so far in history.

At the regional level, the proportion of primary school children to out-of-school children has reduced from 40 per cent to 20 per cent which is huge as a region. However, this prediction has happened against the heavy demographic pressure in the region and in fact that pressure is such that the number of primary school-aged children who are out of school has actually increased to almost the same level as we were in the 1990s. So, this is one issue faced at the system level.

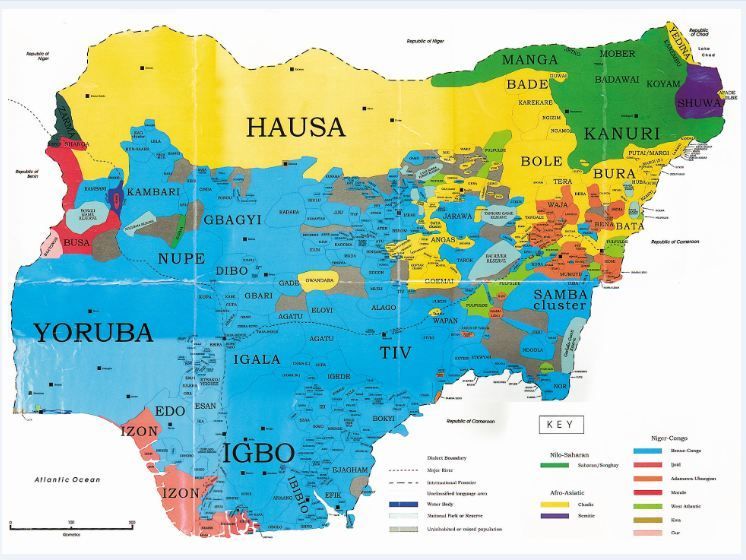

In terms of some of the different factors that children have to face, besides socio-economic conditions which are typical drivers of the difference derived in children’s learning achievement, there are other issues specific to Africa. For instance, Africa’s linguistic diversity is one of the highest in the world. Some countries in the region can have as many as 200 languages; Nigeria I believe has over 400 languages and this causes essential challenges on the language of instruction and the development of teaching and learning materials.

We know that for a child to be able to learn, especially at the foundation level (first six years), they must be taught in the language that they understand, that is their home language. Yet too many children are taught in the language that they do not speak at home. In Africa, only one in five children are taught in their language.

Then there is also the issue of meal conditions not being met for children to learn. Many children are hungry in school with only one in three getting a daily meal. There is also a low level of readiness with few children participating in pre-primary education before being enrolled in a primary school. It is key to note that school readiness is extremely important for future learning, once a child enters into the formal education system.

Another issue is the scarcity of textbooks. Findings have shown that having textbooks as a child increases interest in learning by 20 per cent, however, more than three children in school have to share a book. We have a number of issues that make the learning experience of the African child much more difficult and painful than any other child in the world.

What should be done to address the issues highlighted?

There are a number of ways to address the situation. Currently, in the Born To Learn Report, we recommend a few action points that are directly linked to the points I just made. Some of them are concrete, for instance we recommend giving all children textbooks. We know that in a low resource environment, there are not many educational materials outside of the school environment. This means that children may not have access to textbooks for learning while at home. But by providing textbooks for them it gives them the opportunity to continue their learning experience while at home. We need to collectively ensure that children have teaching materials to continue the learning experiences at home.

Another recommendation is to ensure that children are first taught in their home language before switching to the main language of instruction. Now, this does not mean that we do away with the general (or official) language of instruction, rather we are recommending a bi-lingual education where possible so that children first have an educational experience that starts with the language they speak at home, afterward and progressively, switch to the main language of instruction.

School feeding programmes also need to be implemented. It is unacceptable that today, some children still go to school hungry and they are in many countries. We must remember the saying that there is no learning on an empty stomach.

Another recommendation is enabling access to data. We know that there is a clear lack of data in the region. It is very difficult to have a clear picture of where learning is because there is no data in the region. Not to forget, ensuring teachers are well trained and supported as they are key players in education development.

Essentially, to execute these corrective actions the government needs to make a plan to improve learning outcomes. They need to make it their vision to improve foundational learning as this will ultimately impact future learning.

The last thing I want to say is that there is a lot that can be done at the continental level, in particular, to ensure that countries can learn from their peers. Too often, what we see is a top-down approach where development partners come and say what needs to be done, but what we highlight in the report is that they are ways to redesign the mechanism that allows countries to share their experiences and glean insights on how to implement what has worked and in what context. We know that the African Union is preparing to dedicate 2024 to education. Hence the African Union should use this opportunity to place learning outcomes at the heart of its strategy for Africa.

Photo Credit: Chuma Nwokolo

Introducing indigenous or home languages in the formal school setting as a tool for improving foundational learning is a good suggestion, however, it is not without some critical policy and financial implications. How can Nigeria implement this recommendation?

Your question is extremely difficult because I think Nigeria is probably the most difficult of all the countries to implement this recommendation because of its language diversity, as such it will be pretentious of me to claim to have an answer and, we know this is a difficult policy issue. In many instances, we have seen countries enacting language policies, but as you rightly highlighted, enacting language policies is only the beginning.

You need to develop the curriculum, teaching, and learning materials, invest in teacher education, and also achieve consensus around the policy. In some countries even if bilingual education has been shown to be effective, sometimes the citizens may refuse learning in the language. I can’t give you a possible solution for Nigeria, but let me say this.

What we have seen in Africa overall, is that if we target only 3 per cent of the minority languages, we can reach up to half of the population of primary school age which is effective in terms of cost-effectiveness. For Nigeria, we may not need to integrate all the indigenous languages as a language of instruction. Some countries like the Central African Republic, used vernacular as the home language of instruction. I am sure that in Nigeria, there will be regions with common vernacular language and this could be a starting point. However, to implement this, Africa and Nigeria need to take advantage of its diversities and peculiar contexts.

Very enlightening! Thank you