To mark the 2024 International Day of Persons with Disabilities, the Department of Special Education at the University of Ibadan (UI) in southwestern Nigeria, hosted a guest lecture on Friday, December 6, titled “Transformative Solution to Disability Inclusive Development in Nigeria.”

The Vice-Chancellor, Professor Kayode O. Adebowale, represented by the Dean of the Faculty of Education, Professor M. O. Ogundokun, emphasised the significance of the day, describing it as a reminder of the global commitment to promoting equality and inclusivity for persons with disabilities.

At first glance, the lecture and its theme align with the university’s vision of fostering an inclusive academic environment. However, this vision appears distant for many visually impaired students on campus, who continue to face significant challenges due to inadequate support and resources—particularly the absence of sufficient assistive technology.

Oyindamola Adebayo, a first-year student with visual impairment studying Special Education and English at the University, had a troubling experience during her first ENG 101 (Basic English Grammar) exam. Despite notifying the Department of English about her need for accommodations, she was made to wait outside the exam hall for an extended period, leaving her with little time to complete the test. When finally admitted, the invigilator informed her she would need to use a typewriter—an outdated tool she had neither requested nor knew how to operate.

“I was shocked,” she recalled. “I don’t know how to use a typewriter, and I certainly don’t have one with me. I had to speak up for myself, but it felt like I was fighting for the basic right to have access to proper exam conditions.”

The ordeal was compounded by the state of the room where she was expected to write the exam. “It was dirty and unkempt, with piles of discarded papers and dust everywhere,” she noted. “It was hard to concentrate or perform well under such conditions.”

Adding to her frustration, Oyindamola was forced to find her volunteer interpreter because the faculty didn’t provide one despite prior notification. “It felt like I was being left to handle everything on my own,” she said.

Students with disabilities outside the Department of Special Education face even greater barriers to accessing essential resources. The absence of a dedicated resource centre for such students worsens the challenges they encounter in a system that often marginalises their needs.

For Tunde Onifade, another first-year student in the Sociology department at the Faculty of Social Sciences, the lack of tailored support in the Faculty of Social Sciences translates into daily struggles. As a visually impaired student, he finds himself constrained by the absence of assistive technologies such as screen readers, braille textbooks, or audio materials. “There is no provision for special facilities in my faculty.”

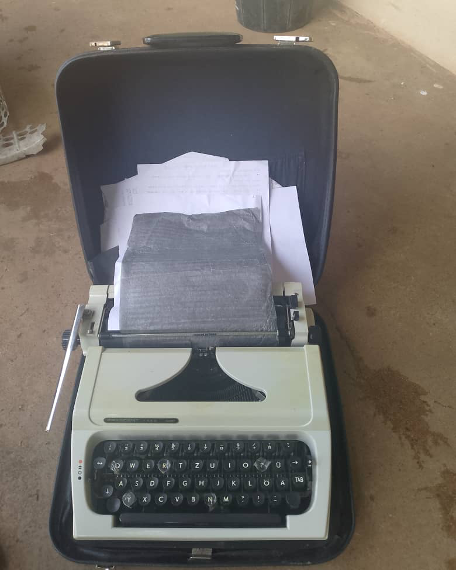

“I have to carry my typewriter from my hostel to my classes every day; assuming there was a provision for that in my faculty, the burden would be lessened,” he told Edugist

On that front, UI’s Department of Special Education has made efforts to provide a conducive environment for visually impaired learners by providing typewriters and braille tools. A newly constructed building, funded by the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund), stands as a symbol of the efforts. This facility includes a resource room with typewriters and basic tools designed to assist visually impaired students during exams. It also provides a designated space for training on the use of these devices.

Yet, these efforts fall short of addressing the actual needs. Despite projects like the construction of the department’s new building, students continue to face significant challenges due to outdated equipment and poor infrastructure.

Special Education’s Limited Reach and Inadequate Resources

Oyindamola Adebayo*, a first-year visually impaired student of Special Education and English at the University of Ibadan, commended the intentions behind the new building but criticised its design flaws. She expressed frustration with the inoperative lifts and poorly constructed ramps, which limit accessibility.

“It’s disheartening to see a new building that still doesn’t meet the basic accessibility needs of visually impaired students. The intention behind the funding was good, but without functional infrastructure, it feels like we’re still being left behind,” she lamented.

While the department provides some support, including a resource room for exams, Oyindamola highlighted the glaring absence of modern assistive technology. “The absence of laptops equipped with screen-reading software like JAWS severely limits independence,” she explained. “We rely on human interpreters to read out exam questions.”

This lack of accessibility becomes apparent during examinations. Visually impaired students often encounter last-minute changes, limited resources, and a dependence on volunteers whose availability is not guaranteed.

Oyindamola believes that the resources made available to them are outdated and advocates for enhanced resources to meet their learning demands. “I have asked the department to consider providing laptops with screen readers instead of typewriters, but it seems nothing will be done about it,” she lamented.

“Typewriters might have been useful decades ago, but in today’s world, they only slow us down, while some facilities exist such as reserved seating in classrooms, these provisions fall short, the equipment here is outdated, and it doesn’t meet our needs,” she explained.

Reflecting on her previous school, Queen’s College, a federal government-owned secondary school in Lagos State, Oyindamola noted the disparity in support. “At Queen’s College, we had all the equipment we needed. But here, it’s a struggle. I even have to dictate answers to someone else because the technology isn’t adequate for me to write exams myself.”

At UI, the shortage of braille machines and updated computers has further compounded her struggle, making exams and assignments more challenging than they need to be.

Oluwamogode*, a 200-level student in the Department of Special Education, echoed similar concerns. “I thought the university would offer better resources, but the reality here is far from ideal,” he said.

Although not visually impaired himself, Oluwamogode works closely with students who are, giving him a front-row seat to the challenges they face. “There are very few interpreters, and those who are available are overburdened. This, combined with outdated equipment, makes studying here incredibly difficult for students with disabilities,” he explained. “What’s even more troubling is the reliance on volunteers who are not always dependable. This leaves students with disabilities to fend for themselves in crucial moments.”

Recently, Oluwamogode had to assist a hearing-impaired student during exams because the department could not find an available interpreter on time.

“Even the Department of Special Education, while doing its best, is limited by a lack of resources. We still don’t have enough tools, and the ones we do have, like typewriters, are not fit for purpose in today’s world. When we ask for more modern solutions, like laptops equipped with screen-reading software, the response is always the same: no money, no resources,” he added.

Mr S.O. Adewumi, an administrator in the Department of Special Education, acknowledged the department’s limitations. “When a student becomes visually impaired, the first step should be rehabilitation. This involves teaching them how to use tools like typewriters, computers with screen-reading software, and even abacuses for calculations,” he explained. He noted that while students are encouraged to acquire personal laptops, this is not feasible for everyone.

The lack of modern training infrastructure adds another layer of difficulty. “If a student doesn’t know how to use a typewriter or computer upon admission, they are dependent on human assistance for exams and assignments. We try to encourage them to learn these skills, but structured training programs are almost non-existent,” he said.

This challenge is worsened by the scarcity of specialised staff. “Not all lecturers are trained in special education. As a result, students often have to arrange for interpreters themselves or rely on volunteers, which is far from reliable,” Mr Adewumi added.

Worse Off in Non-Special Education Departments

While the Department of Special Education attempts to create a more accommodating environment, Oyindamola noted that students with disabilities often feel abandoned by other faculties in the University of Ibadan that do not offer the same level of consideration or resources. Even fundamental provisions, like assigning readers or providing accessible exam formats, are inconsistently applied across the university.

This lack of cross-departmental coordination means that visually impaired students like Tunde Onifade, a first-year student in the Sociology department at the Faculty of Social Sciences, are left in vulnerable positions during exams. Departments frequently make last-minute calendar adjustments during exams, which makes it difficult for special students to adapt.

Without a university-wide accessibility policy, students with disabilities face significant challenges in meeting academic expectations.

Oyindamola’s experience during her ENG 101 (Basic English Grammar) exam is a glaring example of these systemic failures. Despite notifying the Department of English about her need for accommodations, she was made to wait outside the exam hall for an extended period, leaving her with little time to complete the test. When finally admitted, the invigilator informed her she would need to use a typewriter—an outdated tool she had neither requested nor knew how to operate.

“I was shocked,” she recalled. “I don’t know how to use a typewriter, and I certainly don’t have one with me. I had to speak up for myself, but it felt like I was fighting for the basic right to have access to proper exam conditions.”

The ordeal was compounded by the state of the room where she was expected to write the exam. “It was dirty and unkempt, with piles of discarded papers and dust everywhere,” she noted. “It was hard to concentrate or perform well under such conditions.”

Adding to her frustration, Oyindamola was forced to find her volunteer interpreter because the faculty failed to provide one despite prior notification. “It felt like I was being left to handle everything on my own,” she said.

Students with disabilities outside the Department of Special Education face even greater barriers to accessing essential resources. The absence of a dedicated resource centre for such students worsens the challenges they encounter in a system that often marginalises their needs.

For Tunde, the lack of tailored support in the Faculty of Social Sciences translates into daily struggles. Despite his intelligence and determination, he finds himself constrained by the university’s failure to accommodate persons with disabilities (PWDs). “There is no provision for special facilities in my faculty,” he said, reflecting a systemic neglect of the unique challenges faced by PWDs.

Tunde’s reliance on a typewriter exemplifies this neglect. The outdated device, which he must carry from his hostel to his classes every day, symbolises the burdens placed on students like him.

I carry my typewriter from my hostel to my classes every day; it shouldn’t be this way, assuming there was a provision for that in my faculty, the burden would be lessened,

He lamented.

“It’s a Constant Struggle”

“While Special Education does its best, we are constrained by what is available to us; once you step outside this department, it’s as if students with disabilities don’t exist,” Oyindamola remarked. “Students have to rely on personal networks or ad-hoc volunteer arrangements to meet their academic needs… It’s a constant struggle.”

Another significant challenge she faces is the lack of structured support from the institution. “Most of the interpreters who help us are volunteers; they’re not formally assigned by the university,” she explained. This reliance on informal arrangements proves unreliable, leaving visually impaired students dependent on the goodwill of others for basic tasks.

The inconsistency in available support disrupts her academic routine. “It’s hard to know if someone will be available when you need help, and that’s just not sustainable,” she added. This underscores the urgent need for a dedicated and reliable support system to foster an inclusive learning environment.

Bisola Oyinlola*, an interpreter in the Department of Special Education, shed light on the challenges faced by students with disabilities and the gaps in coordination across faculties. “We weren’t even aware there was a candidate in 100-level Sociology, as soon as I got back home, I received a call informing me that there was a student at the DLC centre for the GES exam. The lack of communication and prior notice made it very difficult to provide timely assistance,” she revealed

She stressed the importance of proactive measures from the university. “The admissions office should create awareness and start orientation programs for students with disabilities, informing them about the resources available and how to access them,” she explained.

“Without these steps, situations like Tunde’s will continue to happen,” Mrs Oyinlola added. She is one of the only five interpreters in the university.

Accessibility Challenges on Campus

At the University of Ibadan, accessibility remains a major challenge for PWDs. While some newer buildings—such as Ganduje Hall, the New Faculty Lecture Theatre for technology students, and the CBN Building for pure science students—feature ramps, many older facilities, including the Kenneth Dike Library (KDL) and several hostels, lack essential accommodations. Even in newer structures with ramps, non-functional elevators often complicate access for students who rely on them.

Recent research highlights the extent to which unfriendly physical environments obstruct access to higher education for PWDs. A study conducted by Kitula, Minanago, and Mntumbo at the Open University of Tanzania revealed that facilities such as libraries and laboratories are often located on upper floors, creating barriers for students with physical disabilities. This reality is mirrored at the University of Ibadan, where accessing critical resources remains an ongoing struggle.

The absence of ramps in older buildings complicates mobility, forcing students to rely on others for assistance. Meanwhile, frequent elevator breakdowns in newer structures—intended to improve access—render vital resources inaccessible. In the Kenneth Dike Library (KDL), for instance, the persistent unreliability of the library’s elevator denies students with mobility impairments access to upper floors, where critical facilities such as the Systems Unit, the Closed Access Unit for Arabic Books and Manuscripts Collection, and the e-Research Library are located.

For Oyindamola, who lives with a visual impairment, the library is a daily reminder of institutional neglect. She recalls her first attempt to enter the library for research. “I approached the entrance, but as soon as I saw the stairs, I knew I was in trouble,” she said. With no ramp to provide an alternative pathway, she had no choice but to ask a passing student for help.

This is not an isolated incident. Every trip to the library presents the same hurdle. “It feels as though my needs don’t matter,” she said, reflecting on how such infrastructure oversights make her feel invisible.

Even beyond the entrance, challenges persist. The library’s elevator, which could offer a way for students like Oyindamola to access the upper floors, is often out of service. “I had hoped the elevator would make things easier, but it wasn’t working. I had to wait for someone to help me again. Even then, I felt like I was constantly in the way,” she explained.

Her story reflects the broader struggles faced by persons with disabilities, despite Nigeria’s Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018. The Act mandates that public institutions, including educational facilities, provide accessible infrastructure and reasonable accommodations for PWDs. However, implementation remains slow, leaving students like Oyindamola to bear the brunt of neglect.

“Every time I need to ask for help, it reminds me that I am not being considered in the design of these spaces,” she said. “It’s disheartening, we’re not asking for special treatment; we just want to be seen, included, and supported.”

Building a Truly Inclusive Campus

The lack of accessible infrastructure across Nigerian universities underscores a broader systemic failure. At the University of Jos, located in north-central Nigeria, the Faculty of Education—home to the largest number of students with disabilities—stands as a glaring example. The two-storey building lacks ramps, elevators, and essential assistive technologies, making it difficult for students with mobility challenges to navigate the space independently.

“The university shouldn’t just focus on building new structures; they need to ensure that every building and department is equipped to meet the needs of students with disabilities,” Oyindamola stated.

Both Tunde Onifade and Oyindamola are calling for a university-wide policy that prioritises proactive planning and consistent support across all departments. Their recommendations include the assignment of readers for exams, properly equipped resource rooms, and access to updated technology, such as laptops with screen-reading software.

“We need the university to adopt policies that see us as integral members of the academic community, not as afterthoughts,” Tunde lamented. While the university experience should foster intellectual growth and social inclusion, it often presents numerous obstacles for students with special needs.

Like many Nigerian institutions, the University of Ibadan is overdue for reforms that promote equitable learning environments for all students.

Tunde and Oyindamola’s stories illustrate the broader challenges faced by students with disabilities on campuses across Nigeria, raising questions about the country’s commitment to inclusive education. Although the University of Ibadan has made some progress—such as reserved seating and limited support—the gap between policy and practice remains significant.

“We need more than just token measures; we need real changes that help us learn without being left out,” Tunde emphasised.

For Oyindamola, better-equipped resource rooms could transform the academic experience from struggle to success. “All we want is a fair chance to thrive, just like any other student,” she added, expressing hope that her voice will prompt the university administration to take more proactive steps to support students with disabilities.

Both students envision a campus where visually impaired individuals can move freely, access learning materials in accommodating formats, and take part in assessments without isolation. Small adjustments—such as converting lecture slides into audio formats and providing Braille materials—could significantly improve the quality of life for visually impaired students.

______________________________

This story was produced with the support of the Solutions Journalism Network and the Nigeria Health Watch in partnership with Edugist.