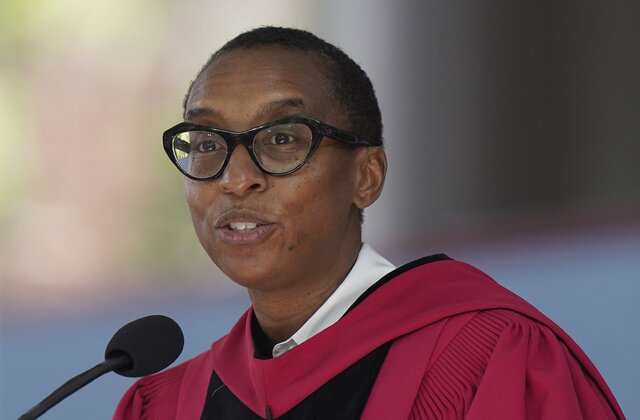

Claudine Gay, Harvard’s first Black president and only its second woman president, resigned from her post on Tuesday amid allegations of plagiarism that follow a firestorm of controversy in recent weeks related to widely criticized testimony last month about antisemitism on college campuses before a congressional committee.

Her resignation marks the shortest presidency in Harvard’s storied history and puts a spotlight on the evolving role of the higher education sector and the limits of free speech on college campuses.

“It is with a heavy heart but a deep love for Harvard that I write to share that I will be stepping down as president,” Gay, who took on the presidency six months ago, said in a statement. “This is not a decision I came to easily. Indeed, it has been difficult beyond words because I have looked forward to working with so many of you to advance the commitment to academic excellence that has propelled this great university across centuries.”

In the weeks following the October 7 surprise attack by the militant group Hamas against Israel, the vast majority of elite schools made a decision to remain silent about the attack, the ensuing war – a stance most institutions of higher education are advised to take and one known as “institutional neutrality.”

FIRE, one of the country’s leading free speech advocacy organizations focused specifically on college campuses, advises colleges and universities to take a neutral stance on issues such as the war between Israel and Hamas, and to explain to students, faculty and the wider campus community that it has an obligation to protect free speech and student safety – and that they won’t be commenting on hot-button political issues in order to avoid chilling students and faculty.

But controversial statements by students and faculty about Israel and the Palestinians drew national headlines, fomenting a broader distrust of the higher education community. As the protests on campuses intensified and reports of antisemitic threats began climbing, so too did calls for college presidents to hold students and faculty accountable, to be clear about what the institutions’ stances are on the war and to draw a hard line against mounting threats targeting Jewish students.

Gay faced particularly intense criticism for Harvard’s response to a letter signed by more than 30 student organizations that declared solidarity with the Palestinians following the attack by Hamas, which declared that the “Israeli regime” was “entirely responsible for all unfolding violence.”

In response, Gay issued a statement condemning “the terrorist atrocities perpetrated by Hamas.” And while she did not criticize student leaders for the letter, she underscored that student opinions were not reflective of institutional stances.

Tensions were boiling over by the time Gay testified before the House Education and Workforce Committee along with fellow presidents Sally Kornbluth of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Elizabeth Magill of the University of Pennsylvania. All three were panned by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle for evasive responses and legalistic answers about what their campuses do and do not tolerate when it comes to antisemitic threats.

Magill resigned two days later.

At the same time, rumors began swirling about problems with citations in Gay’s doctoral thesis from the 1990s, including claims made by conservative policy wunderkind Chris Ruffo that she lifted text from others.

From there, calls only grew for Gay’s ouster – even after the Harvard Corporation, one of the university’s two governing boards, voted to support her continued tenure as president.

“Our extensive deliberations affirm our confidence that President Gay is the right leader to help our community heal and to address the very serious societal issues we are facing,” board members said in a statement at the time.

But as the calls for her resignation from donors and others of significant influence continued, Gay said on Tuesday that it was in the school’s best interest that she resign.

“After consultation with members of the Corporation, it has become clear that it is in the best interests of Harvard for me to resign so that our community can navigate this moment of extraordinary challenge with a focus on the institution rather than any individual,” Gay said in a statement.

The Harvard Corporation said that it accepted the resignation “with sorrow.”

Conservatives cheered the resignation, taking credit for pushing her out and using the moment to bolster some of their culture war claims that the higher education sector – and in particular, elite schools – cannot be trusted.

“All three university presidents gave morally bankrupt testimony at the now infamous congressional hearing to a very specific moral question: Does calling for the genocide of Jews violate your university’s code of conduct,” Rep. Elise Stefanik, New York Republican, said in response to Gay’s resignation. “And one after the other, whether it was MIT, Penn, or Harvard, failed to answer that correctly, instead, bringing up, ‘It depends on the context.’”

Rep. Virginia Foxx, North Carolina Republican who heads the Education and the Workforce Committee said that her committee’s inquiry would continue.

“There has been a hostile takeover of postsecondary education by political activists, woke faculty and partisan administrators,” Foxx said in a statement. “The problems at Harvard are much larger than one leader, and the committee’s oversight will continue.”

Others condemned her resignation, insisting that Gay was pushed out by an ideological, well-monied effort by conservatives, who have been quick to latch on to anything that sullies the reputation of higher education.

“I am saddened by the inability of a great university to defend itself against an alarmingly effective campaign of misinformation and intimidation,” Randall Kennedy, a Harvard legal scholar and one of the university’s most prominent Black faculty members, told The New York Times.

Havard News