What was the turning point for you in your career?

Thank you, my name is Armando. I currently lead the PAL Networks secretariat, based in Nairobi. I started my career as a lecturer in political sciences and never thought I would end up in a classroom teaching grade one and grade two children. I think what really changed my career perspective was the recognition that the youth we are receiving at the university, were struggling with basic concepts, like writing a simple essay.

Or when you ask them to bring a different perspective about a topic, to have an informed debate, you can see young people failing to articulate their knowledge, their perspective, and their viewpoint and to connect with other people’s viewpoints in a constructive way.

This was particularly difficult when it was about writing something. I was having a conversation with my students about one of them who wrote a page with only one full stop. He just got lost somewhere and could not articulate his viewpoint well.

In our university, we started discussing such things as why are our students struggling with the basics, be it in writing or debating. Somehow we noted that the problem was from the foundations.

Children were moving from grade to grade but were not following the required foundations for them to learn and thrive. So, we created a specific unit to cater for foundations. This is how I left the political sciences lectures to start working in the development space, trying to improve the quality of basic services, especially in education.

I don’t know how to keep it short. That unit led to the creation of a civil society organisation working with communities, parents, schools and school management, to discuss why our children are not learning sufficiently to allow them to build more knowledge as they progress. The work that I was doing in Mozambique was similar to what other countries and other organisations were doing, following a citizen-led approach initiated in India and spread over the African continent, to the East and the Americas, such as Mexico.

What we are doing now is engaging citizens to understand that we have a problem with learning outcomes and find local solutions that are contextualised to their living or socio-economic conditions and can solve the problem from the people’s perspective. This is what we do at PAL Network.

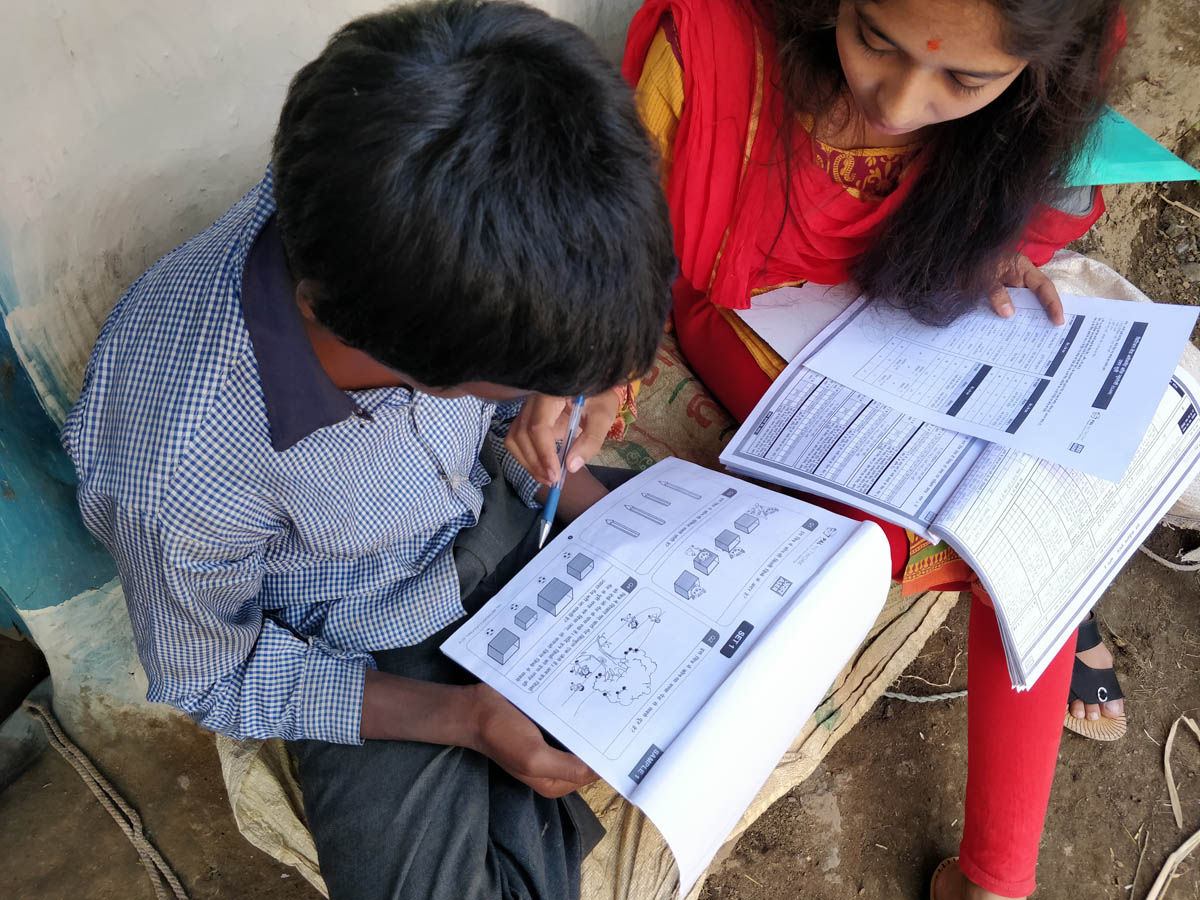

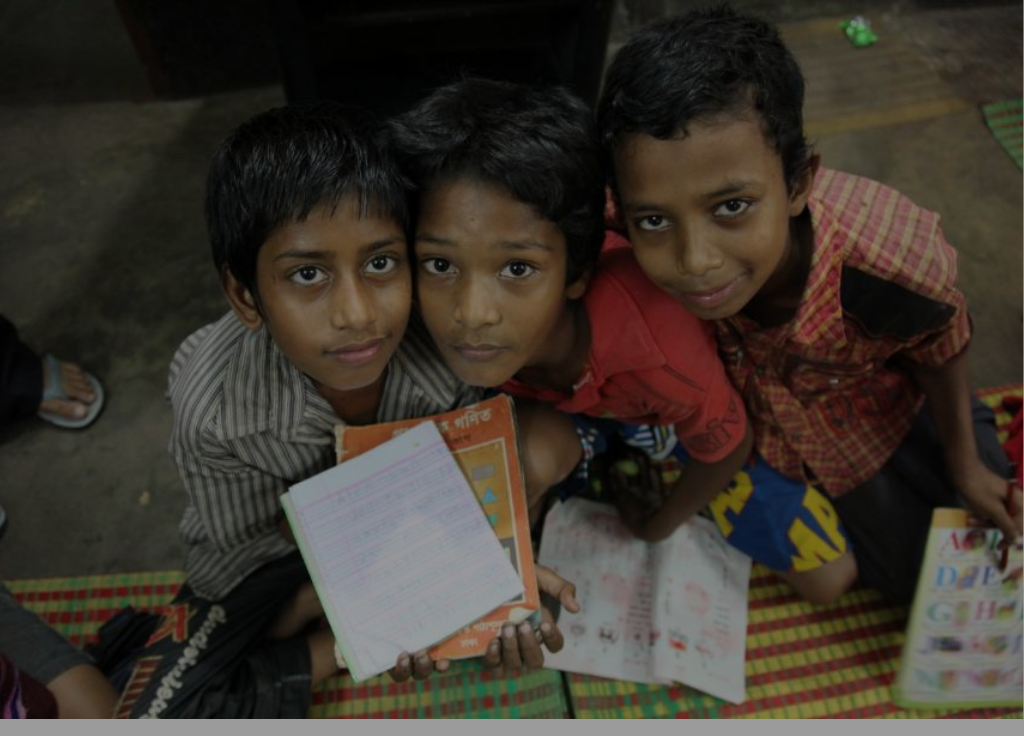

Photo credit: PAL Network

Why is an education that tends to foundational literacy and numeracy important to the global south, Africa and the world?

We started this movement some 17 years ago when a group of mothers, fathers, and volunteers decided to see if their children could read a simple passage and do basic addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

If you remember, 17 years ago, the global discourse was on access to schools, governments, UN systems, and agency donors were all funding the construction of new schools, training more teachers, and making textbooks available.

There was a strong focus on school input. We believe that focus was made based on the assumption that going to school equals learning. But when local fathers and mothers started using a simple test to see if their children could do addition and subtraction, mapped to grade two or grade three, they started to realise that assumption was not true.

We have, especially in the global south many who go to school for five or seven years and still can’t make the basic operations. They still can’t read with comprehension a simple passage. So, realising that schooling is not equal to learning, was a wake-up call that something is wrong with the system.

Our school system is wrong. Something needs to be fixed and that something is building what will make a child learn better. What makes a child learn better is his or her ability to read comprehend and operate numbers, especially the basic operations. We believe that if our children can build the foundations, they can learn other subjects later in life.

And we need to ask ourselves, especially in the global south. How come we are letting our children move from grade to grade, until grade seven and we are not giving them the competencies they require to thrive in life?

What are we prioritising, is it the number of children enrolled in basic education, is it about grades, is it about global statistics to make our countries eligible for funding from donors or UN agencies?

Why are we building a generation of youth without competencies to compete in the market? And we shouldn’t blame others. We need to look into our own systems and see what is it that we need to fix to make the younger generation able to get a better future. We believe that what we need to fix are the foundations of literacy and numeracy for our children.

Photo credit: PAL Network

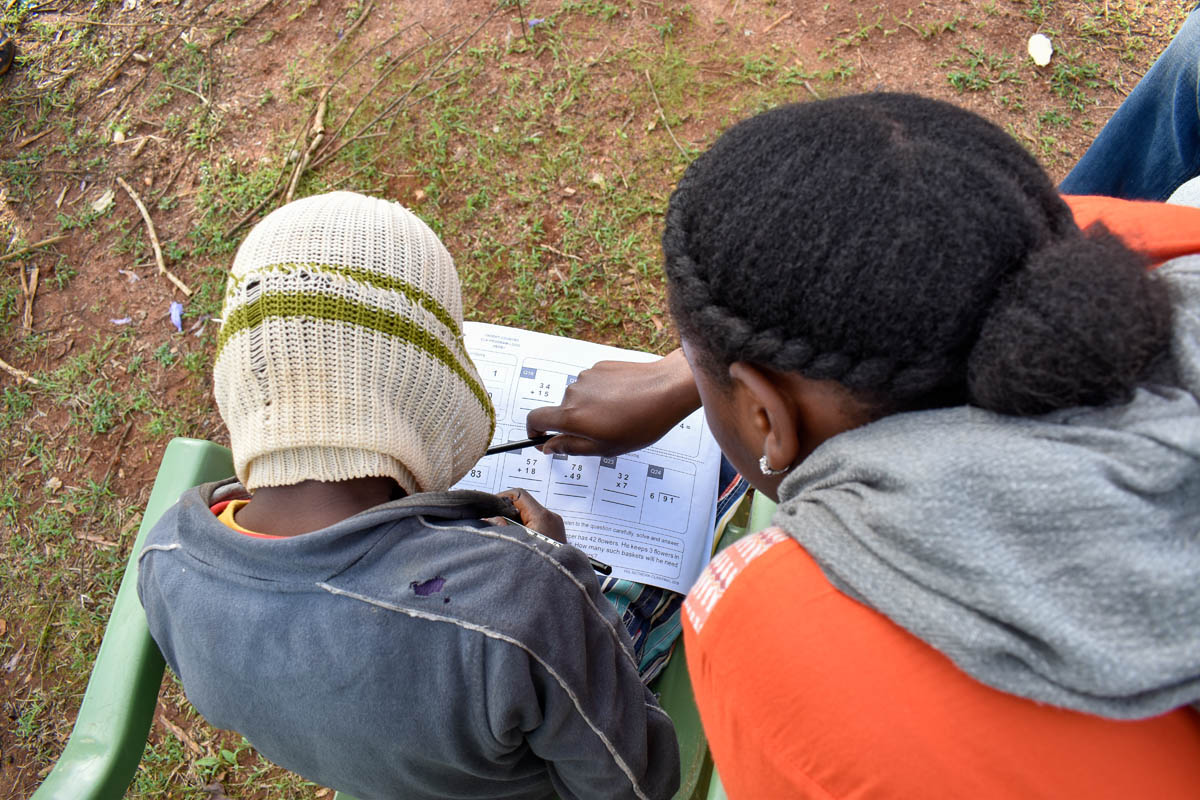

Government support is often required to scale projects in education in addition to civil society organisation, what kind of support have you received from the government?

When we started the citizen-led assessment movement, our relationship with the government was always tense because through this assessment we were able to provide evidence that children were not learning in school, at least not at the level defined by our educational systems.

There was a lot of fighting and questioning of the validity of our data. But with the systems providing the service, and reporting the studies systematically and with our engaging the government in the whole process of designing assessment tools, data collection and analysis, it made them change their opinion because the evidence was strong. The assessments that we use are simple to understand.

After three or five years of consecutive action and discussion about learning outcomes government talked to us and accepted there was a problem and requested we design a solution to the problem. This question was coming systematically in many countries and we decided to explore alternative ways of teaching children to read and the basic maths in short periods of time.

Building also from the experience in India, from teaching with the right method. We started adapting to different countries and working with governments, even the community levels and providing alternative ways of teaching and learning. This proved effective in helping children learn to read and do basic maths in short periods of 30 – 50 days.

This approach on the one hand showing evidence that there is a problem, and on the other hand providing alternative solutions changed the way governments started looking at us.

Photo credit: PAL Network

What does the WISE Awards mean to you and PAL Network?

It is the true recognition of the power of togetherness. This is the first assessment tool that has been developed by the global south citizens from the global south perspective and adjusted to the context.

You know education is dominated by the global north same for the assessment tools and metrics. We came together in a group of 12 to 15 organisations in the global south and from our experience of more than 10 years, we decided to create a simple, reliable and cost-effective assessment of numeracy in Africa.

And the International Common Assessment of Numeracy (ICAN) is a product of years and years of effort at mastery. We could see that if we put our minds together and prioritised what works in our context, and provide solutions that are rooted in our ways of doing, we can reach higher levels and this award is just a demonstration of that.

What is the coverage of your Network and expansion plan?

We are currently represented in 15 countries, South Asia, Africa and America. We have a total of 17 members in those countries on citizen-led assessment or implementing interventions to improve foundational literacy and numeracy.

Our main goal now is to use ICAN, the literacy component of it, what we call ICARE, to build the largest learning assessment tool in the global south. This will be done in 15 PAL Network countries and will have national representatives, providing the most reliable up-to-date figures in the global south in terms of achieving sustainable development goals (SDG4).

The plan is to leverage the experience of ICAN and convert it to large-scale assessment in 15 countries. Definitely, this will be the biggest dataset that can respond to SDG4 in the next few years.

Read also: Qatar Foundation’s WISE to revolutionise education in AI age

What does the 2023 theme for the World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE 11) “Creative Fluency: Human Flourishing in the Age of AI,” mean to you?

I will start by saying this is a new topic to us and as a Network, we have not discussed it in a way that we could form a collective opinion, especially the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in what we do.

There are of course some scepticisms but we see some opportunities, especially when it comes to reaching the most vulnerable and marginalised communities with low resources. There is potential for exploring AI for that purpose but we still need to reflect and position ourselves to see how best to use it in line with ethics and respect for human dignity.

This has been transcribed and edited by Ikechukwu Onyekwelu, managing editor, of Edugist.

info@edugist.org

info@edugist.org